by Denis Tanguay *

Does an M&V Plan "adhere to" or "comply with" the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP)? While this simple question may seem trivial, it can take on a different meaning depending on the context.

Wording such as “comply” or “shall” does not appear in the IPMVP. However, the absence of binding language in the IPMVP does not mean it cannot serve as a compliance document; to the contrary, it can. There is a whole section that describes what adherence to the IPMVP entails. Adherence or compliance will depend on the IPMVP's binding in different situations and contexts.

The binding effect of a document typically requires the approval of a statutory authority, such as a government. But it could also be binding if compliance or adherence is explicitly cited in a financial assistance program, for instance. In context, there are multiple instances worldwide that make the IPMVP a compliance protocol.

Decrypting the M&V Taxonomy

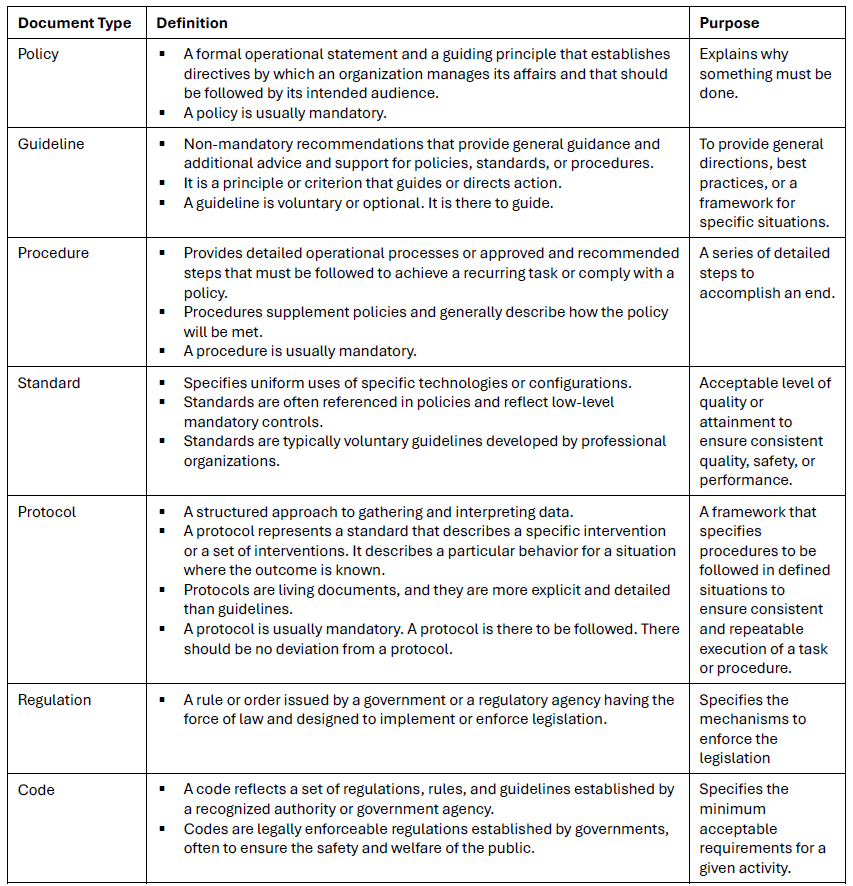

M&V specialists, like most other specialists in their domain, must follow rules in their daily practice. In this regard, written documents providing professional and technical guidance can take many forms, including policies, guidelines, frameworks, best practices, procedures, methods, principles, rules, standards, protocols, regulations, codes, and laws.

Some would argue that these documents have more value than others. Such an argument, faulty at its own face, is based on a misunderstanding regarding the use of each of these document types, stemming from the different processes or approaches that lead to their publication.

To help better understand the issue, let’s start with some definitions.

We may attempt to categorize these terms from least to most important as suggested above. Such categorization would be futile, as very often, the market reality requires following more than one of these document types.

For example, a government may issue a policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This is the “why” for doing something. But then comes the “who”, “what”, “when”, “where”, and “how”.

The “who” can be answered by involving the right professionals and trades in the design and installation of energy-efficient systems, as well as by meeting educational requirements.

“What” could reflect the use of efficient technologies validated by standards.

“When” and “where” could imply using the appropriate energy source at the right place, in accordance with codes, guidelines, and procedures.

And “how” could be having M&V specialists measure and verify the resulting energy savings and GHG reductions by following the specifications of a relevant protocol.

In short, all the above document types play a role in the energy efficiency industry. This role can vary significantly from one jurisdiction to another. And, most importantly, none is hierarchically better than another. They are all important.

What has more value? The process or the outcome?

All the document types listed above define “lines of conduct” for performing tasks. All of these, without exception, are valuable and credible. And this has nothing to do with the process leading to their development and adoption. It involves using the most appropriate reference for any given task.

The actual value comes from the document's effectiveness. Essentially, does the document serve the purpose for which it was written? If yes, every one of them is valuable, period. And the effectiveness is independent of the process leading to the creation and acceptance of a document.

Consider the following.

Many years ago, I headed an association in Canada that presented annual awards for energy efficiency in commercial and institutional facilities. At the time, a government grant was available for energy efficiency projects that would result in a building that was 60% more efficient than the Model National Energy Building Code (MNEBC).

Invariably, in our award contest, any building that did not achieve a 60% performance would not qualify for the award. Yet it was perfectly legal to build a facility whose energy performance met the MNEBC. In short, the same government that set the bare minimum for a building's energy performance was handing out subsidies for buildings that performed 60% above that minimum.

This example highlights the point that codes are often viewed as a minimum required to meet an outcome. For example, building codes essentially codify the bare minimum standards for construction quality. Any best practice above the said building code will produce a better building. Viewed differently, a facility that is aligned with the building code is the worst facility a person is authorized to construct.

Despite all the apparent rigor and formality deployed in its development, a standard that falls short of providing sufficient guidance for achieving its purpose will have little value. On the other hand, a protocol that provides a clear framework and adequate, repeatable procedures to accomplish a task is much more credible and valuable.

Many standards are developed based on consensus. This can also be true of all the document types listed above. However, this does not automatically imply that the process leading to the final document is transparent, even if it involves multiple stakeholders and public consultation.

An official from a national standard organization told me many years ago that in the world of standard development, consensus meant the “absence of sustained opposition.” Essentially, despite broad-based expert input and clear procedural rigour, the outcome could well be the result of exhausting the patience of those opposed.

Ultimately, the consensus could also fall short of providing full directives and guidance to the industry, thereby limiting the effectiveness of a standard. This is why standards are often interpreted as the minimum acceptable level of quality or attainment to ensure consistent quality, safety, or performance.

Arguing that a standard is necessarily preferable to a guideline, a procedure, or a protocol, just on the basis that it rests on some form of structured development process, is thus highly misleading. Such an argument is flawed as it fails to recognize the contextual value of the different document types mentioned here.

ISO 50015 or IPMVP?

The ISO 50015, whose general framework was intrinsically inspired by the IPMVP, does not specify measurement and verification methods for measuring and verifying savings. It is left to the users to define how they intend to perform the M&V and to justify their approach. This could be a reasonable approach, depending on the context and the purpose of M&V.

However, without specifying a method, there is no limit to what someone can come up with, including recommending deemed and stipulated savings without any form of measurement. In such a loosely framed approach, it becomes difficult to discern the methodologies used across various M&V projects, thereby undermining the credibility of reported savings.

Consequently, considering the lack of recommended methods in ISO 50015, M&V professionals and contracting parties to an energy efficiency project will likely choose to follow the IPMVP and rely on one of the four structured, tested, and validated options: A, B, C, or D, as they have been doing it around the world for thirty years now.

This case clearly illustrates that the main advantage of a protocol is that it ensures all interested parties to an M&V project are singing from the same sheet. Additionally, the IPMVP's structured methodology enables comparisons of outcomes across different energy efficiency projects. In programmatic applications, project financing, and GHG reduction validation, this is critical.

A standard that does not provide M&V implementation directives or methodologies and leaves them to arbitrary selection by users is not very helpful in the eyes of many stakeholders, including governments and financial institutions. Why, who, when, what, where, and how are all important questions. A document that tells you that you shall do something but does not provide guidance on how to do it must therefore be used in conjunction with other document types.

To comply or to adhere?

To add a layer of complexity in this discussion, we need to talk about how stakeholders “use” these document types. In the literature, particularly in official documents such as policies, regulations, or legislation, the use of wordings like “in accordance with”, “comply with”, “adhere to”, “follow”, and “conform to” can potentially create confusion.

Section 6 of the IPMVP Core Concepts 2022 provides a detailed outline of what adherence to the IPMVP entails. Emphasis is placed on respecting the six M&V principles: accuracy, completeness, conservativeness, consistency, relevance, and transparency. It also reinforces the critical task of developing a complete M&V plan that covers all the requirements outlined in section 13 of the IPMVP.

Complying usually means an act of doing what you have been asked or ordered to do. It refers to conformity in fulfilling official requirements. On the other hand, adherence suggests doing something required by a rule and does not imply a command. However, it means binding oneself to observance and conformance to the rules.

In essence, when using such expressions, the question we are trying to answer is: how binding is each of the document types mentioned in this article? And the answer is: it depends!

It depends because these terms may have different meanings in the presence of imperative language such as “shall”, “must”, or “are required”. For example, “should comply with the IPMVP” is usually weaker than “must follow the IPMVP” or “shall conform with the IPMVP,” although linguistically “comply” is stronger than “follow” or “conform.”

It also depends on where and how the documents are referred to. The IPMVP is formally cited in the European Union recommendation 2024/2002 on the Energy Efficiency Directive, which suggests that “Member States could encourage enterprises to refer to international protocols or standards such as the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP), ISO 50006, ISO 50015, or EN 16212 to calculate the energy savings or the increase of energy efficiency. These standards and protocols are widely applied in energy management systems and energy performance contracts.”

In this context, someone may use ISO 50006 to establish a baseline and ISO 50015 to obtain guidance on sequencing their M&V efforts; however, they will still need to utilize the IPMVP to select a globally recognized and accepted method for calculating savings. Alternatively, they can skip the ISO series altogether and proceed directly to the IPMVP, which is a standalone protocol.

The Spanish Certificados de Ahorro Energético (CAE, or Energy Savings Certificates) also explicitly refers to the IPMVP. Under this program, CAEs must be validated by ENAC (Entidad Nacional de Acreditación) accredited companies. Official documentation from the Spanish government on the company accreditation scheme mentions that ISO 50047, ISO 17741, or the IPMVP protocol provides content that verifiers can consider in their accreditation application to demonstrate their competency in savings calculation and verification processes.

In the Philippines, following the passage of the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act, the Inter-Agency Energy Efficiency and Conservation Committee adopted a resolution in 2022, directing all government entities, including local government units and foreign service posts, to observe the approved Government Energy Management Program (GEMP) guidelines. The GEMP includes an annex referring specifically to the IPMVP for M&V activities. This document, a “guideline,” is essentially an implementing regulation for the EEC Act. In this case, the use of “soft” wordings such as “guidelines” and “to observe” nevertheless creates a binding obligation for government entities.

Soon, the IPMVP, with EVO's authorization, will also be formally adopted as the national M&V Standard in a European country. The announcement will come in the first half of 2026.

We could list dozens and dozens of such official references to the IPMVP worldwide. Each entity adopting the IPMVP utilizes a range of qualifiers to encourage stakeholders to refer to and use the IPMVP in their M&V activities.

Conclusion

All the document types discussed in this article play a role in the energy efficiency industry. Arguing that one is better than another because of the process used to produce it is short-sighted. The value of a document lies in its usefulness, not in the process of its creation.

How binding is the IPMVP in different situations and contexts? The same question applies to all other document types cited in this article, including standards. The binding degree of a document typically comes with the approval of a statutory authority, such as a government. But it could also be binding if compliance or adherence is explicitly cited in a financial assistance program, for instance. No compliance, no money.

The IPMVP case is insightful. Formally cited in numerous government regulations, referenced by utilities for their grant programs, and mentioned by various agencies, including financial institutions, it dominates the M&V landscape due to its unique framework and options. It has also been the cornerstone of thousands of energy performance contracts worldwide for nearly 30 years.

REFERENCES

Bahadur, Parinita. Difference between Guideline, Procedure, Standard, and Policy. HR Success Guide. January 2014. https://www.hrsuccessguide.com/2014/01/Guideline-Procedure-Standard-Policy.html

Cook, Albert. Policies, Procedures, Protocols, and Guidance: A Care Provider’s Guide. May 2022. Bettal Quality Consultancy. https://bettal.co.uk/understanding-the-difference-between-policies-procedures-protocols-and-guidance-pppgs/

Codes and Standards. Consulting-Specifying Engineer. March 2025. https://www.csemag.com/ebook/codes-standards/

Commission Recommendation (EU) 2024/2002 of 24 July 2024 setting out guidelines for the interpretation of Article 11 of Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards energy management systems and energy audits (notified under document C (2024) 5155)

Daly, Paul. How Binding are Binding Guidelines? An Analytical Framework. Canadian Public Administration. 2023;66:211–229. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/capa.12519

Department of Energy (The Philippines). Inter-Agency Energy Efficiency and Conservation Committee (IAEECC), Resolution No. 5. S. 2022.

Dune, Dr Richard. Policies, procedures, protocols, and guidelines in health and social care. February 2024. https://www.mandatorytraining.co.uk/blogs/dr-richard-dune/policies-procedures-protocols-and-guidelines-in-health-and-social-care?srsltid=AfmBOoox4PKwqVze7oEO-1_1jEv3iRnrvZ__qL3K2sKq8iDCDev3I9vb

Efficiency Valuation Organization (EVO). International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol – Core Concepts (EVO 10000-1:2022), March 2022.

ENAC. Organismos de verificación para el sistema de Certificados de Ahorro Energético (CAE): Esquema de acreditación. RDE-33 Rev. 2, Octubre 2023, Serie 15

Michalsons. The difference between a policy, procedure, standard, and guideline. January 2025. https://www.michalsons.com/blog/the-difference-between-a-policy-procedure-standard-and-a-guideline/42265

Mosedale, Pam. When is a guideline not a guideline? When it’s a protocol! RCVS Knowledge. August 2022. https://knowledge.rcvs.org.uk/document-library/qi-boxset-series-4-when-is-a-guideline-not-a-guideline-when-its/

The Trauma Pro. Guidelines vs Protocols / Evidence-Based vs Evidence Informed. March 2020. https://thetraumapro.com/2020/03/13/guidelines-vs-protocols-evidence-based-vs-evidence-informed/

University of Wisconsin-Madison. Determining Whether a Document is a Policy, Procedure, or Guideline. June 2022. https://development.policy.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1600/2022/01/Policy-and-Procedure-comparison-01-14-22.pdf

(*) Executive Director, Efficiency Valuation Organization