By: Mark Stetz(1), Steve Kromer(2), John Avina(3), Samer Zawaydeh(4), James Waltz(5)

ABSTRACT

Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs) are a key tool for financing energy efficiency projects, yet short contract terms (10–12 years) often exclude capital-intensive, long-payback energy conservation measures (ECMs) needed for deep retrofits and infrastructure modernization. This paper argues that extending EPCs is a vital mechanism for addressing this gap. Drawing on best practices and a cross-case synthesis of U.S. public-sector projects—including federal agencies, municipal housing authorities, airports, and universities—the study develops a framework for credible EPC extensions. The paper demonstrates that successful extensions depend on three principles: baseline integrity, rigorous M&V, and layering additional ECMs onto already verified energy savings. Extensions expand project scope, enabling critical upgrades such as solar PV and chiller replacements while aligning cash flows with long-term sustainability targets, including Kigali Amendment commitments and net-zero objectives. The paper concludes that, when governed by clear policy frameworks and robust M&V, EPC extensions serve as a strategic reinvestment tool that bridges short-term financial constraints with long-term energy and climate goals. Practical recommendations are provided to help practitioners implement extensions while managing legal and performance risks.

KEYWORDS: Energy Performance Contract (EPC); Contract Extension; Measurement and Verification (M&V); Energy Conservation Measures (ECMs); Energy Savings; Baseline Integrity; Baseline continuity; Deep Retrofit.

1. Introduction

In global markets—most notably in the United States—Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs) are often structured with extended terms of 20 to 25 years [1]. Longer durations enable organizations to repay the Energy Service Company (ESCO) with smaller annual payments. This approach minimizes strain on operating budgets, reduces financial risk, enhances financial stability, and guarantees consistent performance over the extended life of the project [2][3]. In certain cases, however, it may be necessary to limit contract terms to relatively shorter durations of 10 to 12 years. Although short-term EPCs can still achieve considerable savings, their reduced repayment durations contribute to financial strain and limit project scope. They also restrict the ability to capture the full economic value of long-term measures. This creates challenges for organizations in aligning operating budgets with broader sustainability objectives.

Extending short-term EPCs offers a practical solution. By moving from a 10 or 12-year contract to 20 years or more, agencies can maintain existing energy savings over a longer term, introduce new Energy Conservation Measures (ECMs) with longer payback periods, upgrade current measures where enhancements are feasible, and strengthen long-term financial viability. In effect, extensions open space for reinvestment, enabling facilities to keep pace with emerging energy-efficiency technologies while meeting evolving regulatory requirements and decarbonization targets.

This paper focuses on the practical considerations and professional judgments involved in extending existing contract terms, and on how such extensions allow parties to adapt investment decisions to changing requirements and technologies.

2. EPC Structure and Investment Tradeoffs

EPCs have long been framed as paid-from-savings projects, where the funding is supported by utility cost reductions and, in some cases, O&M savings. The financing term and interest rate play an important role in determining which measures can be included [4]. When measures are selected, those with the shortest payback periods—such as LED lighting, retro-commissioning, or other HVAC control strategies (e.g., variable frequency drives)—offer faster paybacks. When allowed, these high-return measures can subsidize the lower-ROI ones. In fact, many facility owners are more interested in infrastructure retrofits than in energy savings, since upgrading aging systems directly enhances reliability, occupant comfort, and long-term asset value.

By contrast, measures with longer paybacks—such as chiller or DX unit replacements, and solar PV or EV charger installations—are often excluded, even when they are essential for equipment reliability, occupant comfort, or broader sustainability objectives. For example, lighting retrofits, retro-commissioning, and variable frequency drives typically pay back within three to five years. In contrast, chillers, DX units, and solar projects often require ten to fifteen years to recover their costs.

A project package with an aggregate simple payback of five years might be financeable with a ten-year term, covering interest, O&M, project management, and M&V. A more comprehensive package that incorporates longer-payback measures would consequently extend the overall payback period. Such a deferred-maintenance-inclusive package may only become feasible with longer terms of up to twenty-five years. For this reason, the United States Federal Government allows terms of up to 25 years. The inclusion of provable O&M savings can help justify additional energy measures, and annual M&V provides accountability [1].

By comparison, limiting projects to ten-year terms narrows the scope to only the faster-return measures. While still financially viable, these shorter projects often leave behind critical opportunities to modernize facilities and future-proof operations.

3. Measurement and Verification: The Foundation of Trust

Measurement and Verification (M&V) forms the foundation of trust in Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs), providing a consistent, transparent framework for quantifying and validating savings while safeguarding credibility over time. The credibility of an EPC rests on three interrelated principles: baseline integrity, transparent adjustments, and robust extensions. Together, these three concepts form the foundation of trust in performance contracting. Baseline integrity anchors the measurement, adjustments maintain fairness, and extensions enable growth without undermining credibility.

3.1 Baseline Integrity

Baseline integrity means that energy savings must always be quantified against the same consistent reference point established at the start of the project. If the energy use baseline is reset or redefined, trust in the energy savings calculation may erode. Baseline continuity is particularly important when contracts are extended or additional ECMs are layered onto an existing agreement. Maintaining the original baseline is a way to ensure that energy savings remain cumulative and verifiable, rather than fragmented across multiple contract periods. This continuity is essential not only for accurate accounting but also for sustaining the confidence of investors, auditors, and regulators. Without it, extensions could be perceived as manipulating results or double-counting savings. With it, extensions become a credible mechanism for sustaining long-term energy performance and financing deeper retrofits.

3.2 Measurement and Verification in Practice- Adjustments

Adjustments are the transparent and mutually agreed methods used to account for changes in conditions that are outside the control of the EPC parties, such as weather variations, occupancy changes, operating hours, or functional changes to the facility. These adjustments protect the integrity of the baseline by ensuring that reported savings reflect true efficiency improvements rather than external influences.

In longer-term contracts, and particularly in extended EPCs, exposure to non-routine adjustments increases. Facilities evolve over time, operational requirements change, and systems may be repurposed. Without a structured and well-documented adjustment methodology, these changes could undermine confidence in the reported savings.

The credibility of any EPC also depends on the ability to measure and verify (M&V) energy savings with confidence [7][8]. International protocols, such as the IPMVP [9], provide guidance on M&V approaches. These protocols ensure that baseline conditions are documented, adjustments are applied transparently, and energy savings calculations remain consistent across reporting periods. By adhering to recognized protocols, projects maintain accountability and comparability, regardless of contract length or technology type.

M&V also plays a critical role in contract extensions. When existing ECMs are carried forward into a longer term, or when new measures are layered onto prior savings, M&V assures continuity. It verifies that previously documented energy savings persist, while also integrating the impact of additional measures. In this way, M&V protects both the owner and the ESCO, aligning financial flows with technical performance over time. Annual M&V reports serve as the accountability mechanism, confirming that avoided energy costs are sufficient to cover debt service and other contractual obligations. If performance drifts, M&V provides the evidence needed to inform corrective actions, adjustments, or remedies.

One area of concern is with non-routine events, such as changes to building operations and controls. Although annual checks for such events should already be standard practice, contract extensions make it especially critical to confirm that the original baseline assumptions remain valid. Hence, re-commissioning should be performed, and an ongoing annual review of HVAC and central plant controls should be undertaken by the ESCO to maintain the energy savings sequences and setpoints.

3.3 Term Extensions

Extending terms for future EPCs is relatively straightforward, but the greater challenge lies with projects already implemented under contracts limited to shorter terms. Many of these projects excluded valuable measures simply because they pushed the aggregate payback beyond the allowable limit. Extensions provide an opportunity to revisit those decisions and incorporate measures that were previously out of reach.

Contract extensions also allow for upgrading existing ECMs as technology improves. For example, a 100-watt LED that replaced a 400-watt high-pressure sodium lamp a decade ago might now be replaced by a 50-watt LED with even greater efficiency and integrated controls. Extensions give agencies contractual flexibility to capture these improvements and layer them onto already verified savings, also referred to as cost avoidance (i.e., avoided utility costs that cover repayment).

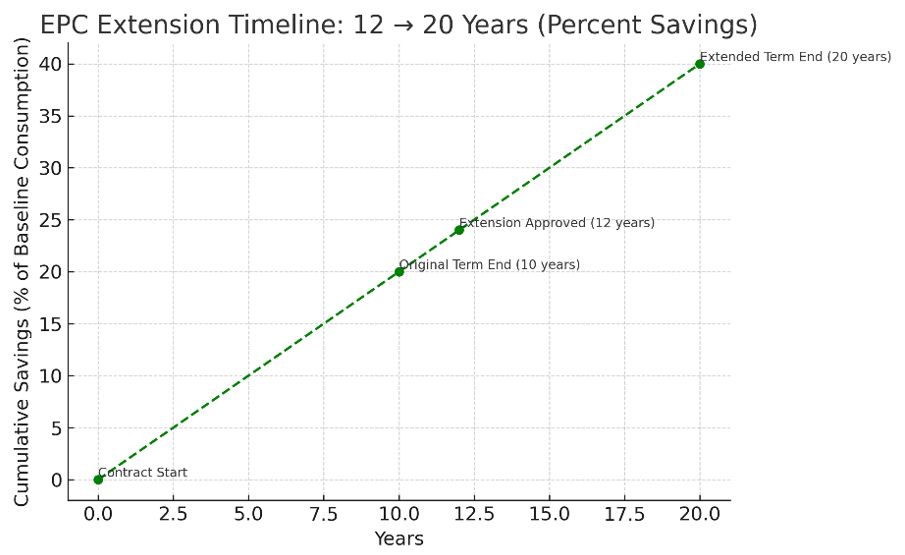

Consider a project that initially identified two ECMs: a lighting retrofit with a three-year payback and a chiller replacement with a fifteen-year payback. Under a ten-year contract, it is possible that only the lighting upgrade could be approved. If policy later allows a twenty-year term, the chiller could potentially be added in a second phase, with energy savings from both measures combined to support the extended contract as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. EPC Extension Timeline expressed as cumulative savings

Contract extensions also enable more comprehensive retrofits, which in turn support the achievement of sustainability objectives, including alignment with the United States’ net-zero emissions target by 2050 [5] and compliance with the Kigali Amendment, which obligates participating countries to reduce the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of refrigerant gases. Under the Kigali framework, nations must phase down high-GWP hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and transition to low-GWP alternatives [6]. This transition will necessitate replacing many existing cooling systems within the next 15 years with high-efficiency technologies that utilize refrigerants with a GWP approaching one.

Contract extensions also facilitate the transformation of facilities toward building code compliance, enabling the implementation of essential upgrades—missed during the initial contract term—to HVAC systems, building envelopes, lighting, ventilation, and other systems that fall short of regulatory requirements. Many facilities currently operate with non-compliant infrastructure, and without a structured financing mechanism, owners often defer these upgrades due to budgetary constraints. By extending the contract term, owners can integrate code-mandated improvements within the performance contract framework, using ongoing energy savings to offset capital costs. This approach not only ensures required compliance with national building codes but also safeguards long-term operational efficiency and occupant comfort without imposing additional financial burdens on facility budgets.

One important caveat is equipment service life. ECMs introduced during an extension must remain effective for the full duration of the extended term. A chiller with a twenty-year useful life or a solar PV system with a twenty-five-year useful life is well-suited, whereas an LED system with a ten-year lifespan may require replacement with the contract extension. These considerations must be addressed early to ensure credibility and to avoid overpromising energy savings that cannot be sustained throughout the extension period. A full life-cycle cost analysis may help identify these issues.

4. Case Examples

4.1 United States Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

One of the clearest examples comes from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD’s) statutory authority, where Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) were granted the ability to extend contracts from 12 to 20 years [10][11]. Federal policies have reinforced EPCs through the Energy Policy Act of 2005 [12] and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008 [13], ensuring their continued use as a financing mechanism for energy efficiency projects. In addition, HUD regulations incentivize Public Housing Authorities to reduce utility costs through energy conservation and rate reduction measures under 24 CFR §990.185 [14]. Such regulations allowed housing authorities to integrate additional ECMs mid-contract while continuing to rely on already-verified energy savings. Agencies such as the King County Housing Authority (KCHA) leveraged this flexibility to add heat pumps, LED retrofits, exhaust fans, and ERVs—yielding deeper retrofits, greater energy savings, and improved resident comfort.

4.2 Municipal Housing Authority Extensions

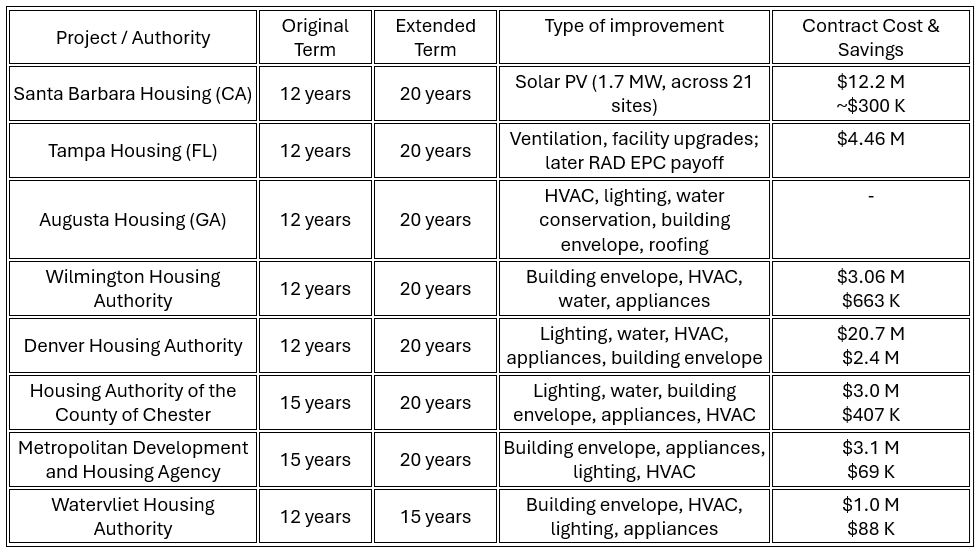

Several local housing authorities have used extensions to expand the scope of work beyond the limits of their original EPC terms. More details are provided in the following case examples.

4.2.1 Santa Barbara Housing (CA)

Extended its EPC by adding a 1.7 MW solar PV project across 21 sites, generating 2.6 M kWh/year and saving ~$300k annually, while preserving baseline continuity [15].

4.2.2 Tampa Housing (FL)

Extended its EPC to a 20-year term at J.L. Young Gardens (a 449-unit senior community), financing ventilation and facility upgrades under the extended contract. Later Rental Assistance Demonstration program conversions included paying off remaining EPC debt (~$4.46M) to reset the financing structure [16].

4.2.3 Augusta Housing (GA)

Extended its EPC via a Phase II package adding ECMs (lighting, water conservation fixtures, HVAC retrofits with instantaneous gas water heaters, window and door replacements, weather-stripping, plus re-roofing at multiple sites and improvements at 8-10 developments (e.g. Oak pointe, Allen Homes, Barton Village), and lengthened the term by 8 years (12 → 20) to finance these deeper retrofits—while preserving original baseline [17].

More examples of HUD Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) extensions and applications are listed in Table 1, as documented by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) [18]. These cases illustrate how various housing authorities across the United States have implemented EPCs, extended contract terms, and layered new ECMs to achieve long-term utility cost savings and improved building performance.

Table 1: Case Examples from HUD

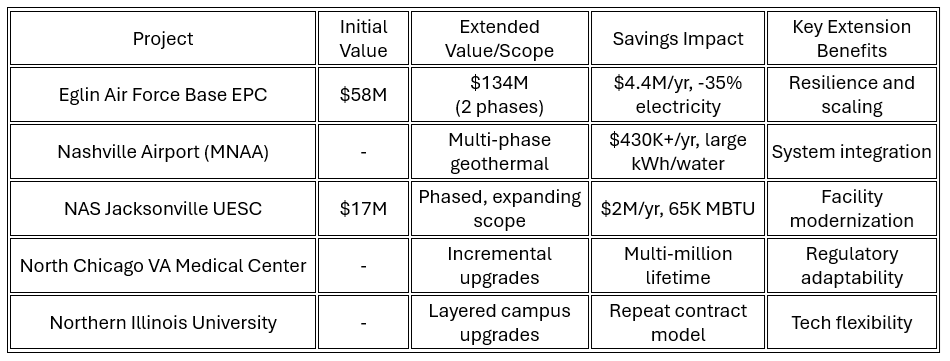

4.3 ESG Multi-Phase Extensions

Beyond HUD and municipal housing authorities, extensions are widely used in multi-phase projects led by Energy Systems Group (ESG). These projects—spanning federal installations, airports, universities, and medical centers—show how phased extensions enable clients to respond to evolving resilience requirements, adapt to regulatory changes, and pursue deeper savings and evolving sustainability goals—often without new procurement processes. The phased contract structure, extensions, and additions are foundational to ESG’s repeat client rate and are illustrated in the following project summaries [19][20][21].

4.3.1 Eglin Air Force Base EPC

The Eglin EPC exemplifies contract extension as a scaling strategy. Initially awarded in September 2018 ($57.8M), the contract was extended in March 2019 through an add-on phase, growing the total value to $134 million. The extension allowed Eglin to reinvest early savings and lessons learned into additional upgrades—expanding from LED retrofits to advanced CHP and microgrid functionality. Base leadership used the flexibility inherent in EPC contract language to respond to evolving resilience and security priorities. The extension was integral in achieving energy assurance through fixed pricing, manual generator switches, and distributed generation, demonstrating the value of ongoing partnership over one-time implementation [19].

4.3.2 Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority (Nashville International Airport)

ESG partnered with MNAA through a multi-phase expansion model. Each round of improvements built on previous work, allowing enhanced system integration and greater overall savings than a single-phase effort could accomplish. The geothermal lake plate cooling system emerged as an add-on to early airport energy programs, enabled by the airport’s proven success and willingness to extend prior agreements. These iterative extensions resulted in reduced kWh demand, annual water savings, and utility cost reductions of more than $430,000 per year without restarting lengthy procurement cycles. The airport leveraged extensions to address technology changes, support unprecedented growth, and maintain leading-edge status in sustainability [20].

4.3.3 Naval Air Station Jacksonville (NAS Jacksonville)

A phased, extensible UESC at NAS Jacksonville enabled regular scope additions, such as new buildings, lighting system upgrades, and further retro-commissioning. Contract language provided mechanisms for extensions to the original $17 million scope, supporting repeated modernization across a diverse set of facilities. These add-on phases, rather than one-off projects, promoted strong utility partnerships and uninterrupted operations, resulting in $2 million per year in savings and over 65,000 MBTU annual energy reduction. Each extension advanced mission readiness, reliability, and tenant satisfaction because they were custom fit to changing operational needs [21].

4.3.4 North Chicago Veterans Affairs Medical Center

ESG worked with VA medical centers under a series of extensions across multi-phase agreements [22]. Specifically for North Chicago Veterans Affairs Medical Center, ESG delivered a two-phase on-site energy center under an Enhanced-Use Lease—Phase I $13.6M, Phase II $15.7M (5/21/2002–2/1/2005)—with 2 MW of generation, 2 HRSGs, 3 package boilers, and 250,000 lb/hr steam capacity serving the VA campus and adjacent Navy barracks; scope also included BAS/HVAC controls and chilled-water replacements, yielding a more secure, self-sufficient supply, reduced energy and O&M costs, and a revenue share to VA from non-VA energy [23].

4.3.5 Northern Illinois University

NIU illustrates how repeat extensions and add-on phases enable continuous campus modernization. ESG delivered 11 phased EPC projects (2000–2017) across 40+ buildings—from campus-wide lighting redesign/retrofits (more than 40,000 fixtures) and HVAC/BAS upgrades (Convocation Center, valves, steam traps) to West Chiller Plant, window/door replacements, piping insulation, roofing, and solar panels for swimming pools. The total program value was around $64M, with more than $4M per year in reported savings and more than $200M in lifetime energy savings, plus 425,525 metric tons of CO₂ reduction [24].

Table 2: Summary Table for ESG extended projects:

5. Financial Implications

The length of an EPC has direct consequences for its financial structure. The terms of the contract influence what measures can be included, how risk is allocated, and how cash flows align with debt service. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for both owners and financers.

Shorter terms (10–12 years) create pressure to rely on quick-payback measures such as lighting or HVAC controls. While these projects can be financed reliably, they often exclude capital-intensive measures with longer paybacks. Short terms also increase annual debt service requirements, which can strain operating budgets even if total cost avoidance is sufficient.

Longer terms (15–25 years) spread repayment over a greater period, reducing annual debt service and enabling inclusion of longer-life ECMs such as chillers, central plant upgrades, or solar PV generation. The trade-off is greater exposure to long-term uncertainties, including interest rate shifts, technology performance, or changes in facility use.

Interest rates and financing costs interact closely with contract term length. A low-interest environment makes longer contracts attractive because carrying costs remain manageable over time. In contrast, when rates rise, the benefits of term extension may diminish, and owners may prefer shorter contracts with reduced total financing costs.

Measurement and verification requirements also influence financial implications. Robust post-retrofit measurement and verification followed by annual M&V can reassure lenders and justify longer terms by ensuring that energy savings (i.e., cost avoidance) remain credible. Conversely, weak or inconsistent M&V erodes confidence and may force contracts toward shorter durations regardless of owner preference.

Financial modeling tools provide a structured way to test these trade-offs. By simulating different contract terms, interest rate scenarios, energy price trajectories, and ECM packages, owners and financiers can compare outcomes before committing to an extension. These tools make the trade-offs transparent, highlighting how assumptions about escalation, degradation, O&M burdens, and useful life shape long-term viability.

Extensions and phased additions provide one mechanism for balancing these trade-offs. They allow owners to start with a manageable package and expand scope over time, while lenders retain confidence in repayment flows anchored by verified savings.

6. Policy and Strategic Implications

Policy frameworks enabling EPC extensions are crucial for bridging the gap between financial realities and long-term sustainability goals. By embedding flexibility into contracting structures, they allow organizations to pursue efficiency and decarbonization without undermining fiscal viability.

One of the clearest precedents comes from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Through the Energy Policy Act of 2005, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008, and implementing regulations at 24 CFR § 990.185, HUD granted Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) the ability to extend EPC terms from 12 to 20 years [12][13][14]. This statutory authority provided a model for how extensions can be codified in federal policy, while maintaining accountability through required M&V and a utility subsidy “freeze” mechanism that caps or holds utility subsidies at current levels to prevent cost increases.

The HUD framework demonstrates that policy can:

- Enable deeper retrofits by accommodating long-payback ECMs.

- Reduce administrative burden by avoiding repeated procurements and allowing phased add-ons.

- Maintain accountability through baseline continuity and annual M&V.

- Provide a replicable model for other agencies and jurisdictions.

EPC extensions should therefore be viewed not only as financial mechanisms but also as strategic policy instruments. When supported by clear statutory authority and robust M&V requirements, they provide a pathway to align fiscal discipline with broader energy and climate objectives.

7. Legal Risks and Remedies in EPC Extensions

Contract extensions raise important legal considerations, as they alter the balance of rights and obligations between the owner and the ESCO. The degree of risk depends heavily on the sector and the governing legal framework.

- Government contracts are constrained by federal acquisition rules. Extensions must comply with statutory authority, and risks include exposure under the False Claims Act, mandatory disclosures, and strict audit requirements.

- MUSH market contracts (municipalities, universities, schools, hospitals) are governed by state and local procurement laws. Extensions may be negotiated but remain subject to public oversight. Key risks include M&V disputes, ownership of equipment, and compliance with local finance regulations.

- Private sector contracts are the most flexible, with extensions negotiated directly between parties. Risks focus on performance guarantees, insolvency, or change-of-law issues, with remedies enforced through litigation or arbitration.

- Central lesson: extensions are only as durable as the legal framework supporting them. Clear statutory authority (as in HUD), well-drafted contractual provisions, and robust M&V are essential to minimize disputes. Where these are absent, extensions may be viewed as overreach, unenforceable modifications, or improper circumvention of procurement rules

Table 3: Comparative Table for Legal Risks and Remedies

8. Recommendations for Practitioners

To ensure that EPC extensions deliver both financial and technical credibility, practitioners should adopt a systematic and disciplined approach. The following recommendations represent best practices drawn from federal guidance, industry protocols, and lessons learned from public sector case studies.

- Establish and Document Baselines at Project Inception—and Preserve Them.

A rigorous baseline is the foundation of every EPC. Establishing it rigorously at project inception and documenting the methodology in detail ensures transparency and credibility. Equally important is preserving that baseline throughout the life of the project, even as extensions are added. Without a consistent reference point, savings claims can be questioned, undermining both the financial and technical integrity of the contract.

- Do Not Reset the Baseline During Extensions; Consistency is Key.

Resetting baselines can introduce risk by erasing the history of verified savings and increases the likelihood of double counting. For this reason, practitioners should maintain the original baseline across both the initial term and any extensions, thereby avoiding any baseline resets that may undermine energy savings credibility. This practice aligns with DOE and EVO guidance, which emphasizes the importance of continuity to protect accountability and investor confidence.

- Apply M&V Protocols (e.g., IPMVP) Across Both Original and New ECMs.

Measurement and Verification (M&V) must be applied consistently, regardless of whether an ECM was part of the original contract or introduced during an extension. Using recognized protocols such as EVO’s International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP) ensures comparability and credibility of reported savings. Inconsistent application of M&V can weaken trust among stakeholders, particularly financiers and regulators.

- Retro-commission the HVAC and Central Plant Controls Annually

Longer EPC projects often suffer from degradation in the effectiveness of energy savings control strategies. O&M staff, in response to occupant complaints, often override the controls strategies implemented by the ESCOs, resulting in reduced actual annual energy savings. It is even more important that with longer contract terms ESCOs perform annual retro-commissioning on HVAC and central plant controls to ensure that efficient controls settings remain in place so that the buildings achieve the intended energy savings.

- Require Two to Three Years of Verified Energy Savings Before Approving an Extension.

Allowing sufficient time for original ECMs to demonstrate performance is critical. A minimum of two to three years of verified energy savings provides a reliable performance history that can be used to justify an extension. This practice mitigates risk by ensuring that energy savings are real, persistent, and not influenced by temporary anomalies such as weather fluctuations or operational changes.

- Use Extensions as Opportunities to Layer ECMs Strategically.

Extensions should not be viewed as administrative exercises but as strategic opportunities to broaden the project scope. Practitioners can layer in longer-payback ECMs, upgrade existing measures with newer technologies, and introduce smarter control systems to enhance performance. For example, adding solar PV, replacing aging HVAC systems, or upgrading lighting with next-generation LEDs can transform an extension into a driver of a greater energy savings, improved reliability, and enhanced occupant comfort.

- Ensure All Approvals, Resolutions, and Financial Records Are Fully Documented.

Documentation is central to credibility. All approvals, whether from governing bodies, financing authorities, or oversight agencies, must be formally recorded. Financial records, repayment schedules, and M&V reports should be archived in a transparent, secure, and accessible manner. This not only strengthens accountability but also establishes a clear audit trail for future stakeholders who may need to review or evaluate the project.

9. Conclusion

EPC extensions represent more than contractual adjustments—they serve as mechanisms for aligning short-term financial structures with long-term operational and sustainability goals. By allowing projects to incorporate additional measures midstream, extensions preserve the credibility of existing energy savings while enabling deeper retrofits and adoption of new technologies.

The decision to extend a contract requires careful evaluation of baseline integrity, transparent adjustments, and robust M&V to ensure that energy savings remain credible over time. Equally important, it requires consideration of equipment useful life (EUL), remaining useful life (RUL), and lifecycle costing, so that commitments made today remain viable throughout the extended term.

Policy frameworks such as HUD’s statutory authority demonstrate that extensions can be codified in a way that balances flexibility with accountability. Financial modeling illustrates how contract term length interacts with interest rates, debt service, and long-term risk. Legal frameworks define the boundaries of permissible extensions and the remedies available when performance falls short.

When approached with rigor, extensions are deliberate reinvestment strategies. They allow owners to adapt to evolving technologies, respond to regulatory and market changes, and achieve long-term decarbonization objectives. The challenge is to balance opportunity with discipline—ensuring that every extension strengthens, rather than undermines, the credibility and value of performance contracting.

REFERENCES

- IEA (2018), Energy Service Companies (ESCOs), IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-service-companies-escos-2, License: CC BY 4.0

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). (2019). Financing Energy Improvements in Public Sector Buildings: EPC Best Practices.

- Waltz, J. P. (2003). Management, Measurement, and Verification of Performance Contracting. Fairmont Press.

- S. Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP). (2025). About Federal Energy Savings Performance Contracts. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/femp/about-federal-energy-savings-performance-contracts

- The White House. (2021). Executive Order 14057: Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability. Washington, DC.

- United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). (2016). The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol: HFC Phase-down. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Stetz, M. (2021). Measurement and verification principles in energy performance contracts. ASHRAE Journal, 63(8), 18–27.

- Kromer, S. (2024). The role of the measurement and verification professional: Judgment and decision-making in the application of M&V. River Publishers.

- Efficiency Valuation Organization (EVO). (2022). International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP).

- S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (2009). Public Housing Operating Fund Program; Increased Terms of Energy Performance Contracts. Federal Register, 74 FR 4242.

- S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (2011). Guidance on Energy Performance Contracts. PIH Notice 2011-36.

- Energy Policy Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-58, §151, 119 Stat. 594 (2005).

- Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-161, §229, 121 Stat. 1844 (2007).

- 24 CFR §990.185 – Utilities expense level: Incentives for energy conservation/rate reduction.

- S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (2012). Renewables in Practice: Santa Barbara County Housing Authority Case Study. Washington, DC: HUD. Available at: https://www.hudexchange.info/sites/onecpd/assets/File/Renewables-in-Practice-Case-Study-Santa-Barbara-County-Housing-Authority.pdf

- S. Department of Energy. Tampa Housing Authority: J. L. Young Gardens Better Buildings Solution Center Showcase Project. Available: https://betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/showcase-projects/tampa-housing-authority-j-l-young-gardens?utm

- Augusta Housing Authority. (2013). 5-Year/Annual Plan (2013–2017) includes Phase II EPC extension (8 years) and ECM scope. Augusta, GA. Available at: https://forms.augustaga.gov/WebLink/DocView.aspx?dbid=0&id=25782&page=6

- S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) (2017). Energy Performance Contracting in HUD’s Public Housing: A Brief Overview. Washington, DC: Office of Public and Indian Housing. Available at: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/EPC.pdf

- S. Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP). (2019). Eglin Air Force Base Comprehensive Energy Assurance Project Wins FEMP Contracting Award. Washington, DC: U.S. DOE. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/femp/eglin-air-force-base-comprehensive-energy-assurance-project-wins-femp-contracting-award

- Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority (MNAA). (2016, May 17). Airport Authority Completes Installation of Largest Geothermal Lake Plate Cooling System in North America. Press release. Available at: https://flynashville.com/press-releases/airport-authority-completes-installation-of-largest-geothermal-lake-plate-cooling-system-in-north-america.

- Energy Systems Group (ESG). (2011). Naval Air Station Jacksonville Project Profile (Federal Government). Available at: https://fl.energyservicescoalition.org/Data/Sites/1/documents/casestudies/FL%20-%20NAS%20Jacksonville.pdf

- Energy Systems Group. (2025). VA Medical Center upgrades power systems for energy reliability. [LinkedIn post]. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/energy-systems-group_veteransupport-vamedicalcenter-energyefficiency-activity-7310654348806475776-Vzxz

- Energy Systems Group (ESG). (2023). North Chicago Veterans Affairs Medical Center (IL) Case Study. PDF. Available at: https://energysystemsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/North-Chicago-Veterans-Affairs-Medical-Center-IL-Case-Study.pdf

- Energy Systems Group (ESG). (2023). Northern Illinois University (IL) Case Study. Available at: https://energysystemsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Northern-Illinois-University-IL-Case-Study.pdf

(1) Mark Stetz, Principal, Stetz Consulting LLC

(2) Steve Kromer, Energy Efficiency Consultant

(3) John Avina, President, Abraxas Energy Consulting

(4) Samer Zawaydeh, Consultant

(5) James Waltz, President, Energy Resource Associates, Inc.

Table of contents image by Aymane Jdidi on Pixabay.