![]() By Eric Mazzi*

By Eric Mazzi*

Behavior change1 is growing in importance in multiple fields of resource conservation, including energy savings.2 Perhaps the most common application today of behavioral interventions is through integration into Strategic Energy Management (SEM) programs. Like any interventions intended to produce energy (or peak demand) savings, individuals and organizations rightfully want to know what energy savings have been achieved. That’s where our M&V community comes into play. In this article I share some experience and perspectives on M&V for behavioral programs as applied to commercial and industrial (C&I) facilities. I use examples from M&V of a pilot behavior change program at Atrium Health to illustrate some of the challenges and unique attributes of M&V for behavioral interventions in C&I facilities.3

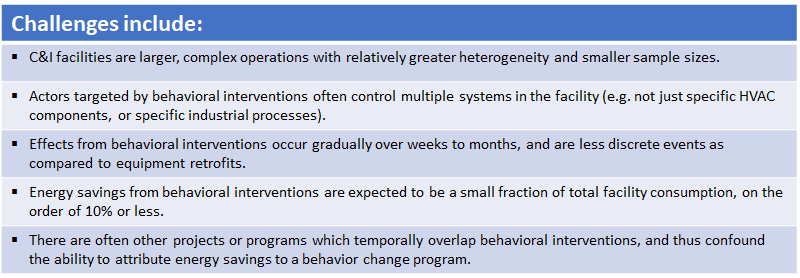

Assessment of energy savings due to behavior change has most often focused on households, characterized by large populations of relatively homogeneous facilities with 103 to 106 customers. Behavior change in households is amenable to the application of a wider variety of research approaches such as randomization, use of controls, and matching.4 But the unique characteristics of behavior change when combined with C&I operations presents unique conditions which limit the range of available methods to quantify energy savings.

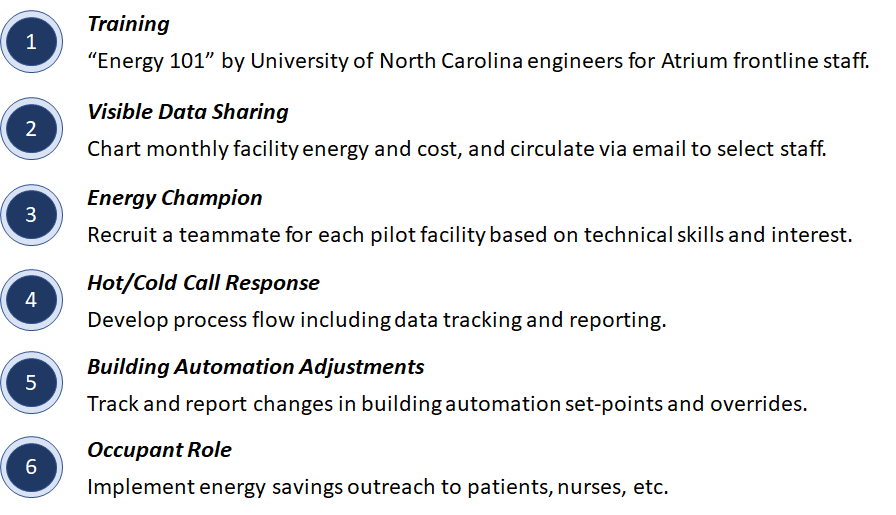

Atrium Health is one of the largest healthcare networks in the U.S., headquartered in Charlotte, with over 62,000 employees in more than 900 facilities including 47 hospitals. In 2016 Atrium embarked on a behavior change pilot program, Energy Connect. Six facilities were chosen for the pilot, with six strategically-chosen behavioral interventions. Details on the design and qualitative evaluation of Energy Connect are documented in an ACEEE paper.5 The six chosen behavioral interventions are:

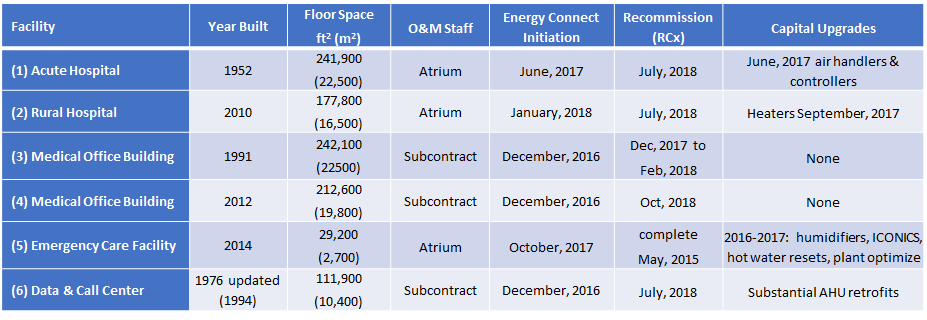

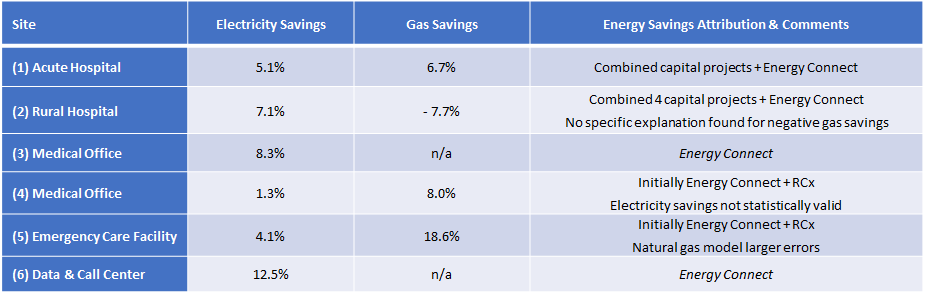

Table 1 summarizes key attributes of the six pilot facilities, staffing, and activities affecting energy consumption.

Table 1: Facility attributes and activities for Atrium Health’s Energy Connect pilot program.

Based on the challenges identified above, and project attributes in Table 1, the chosen M&V method was a pre- versus post-intervention approach using IPMVP Option C. The baseline period for each facility was set as the 12 months preceding the first Energy Connect intervention (training). All facilities consume electricity, with some having hourly data and some only monthly. Four facilities consume natural gas, some with daily data and some monthly. As of the date of this article, not all six interventions have been implemented, and the targeted reporting periods are not all complete. Regression models were developed using heating degree days for gas, and cooling degree days for electricity (other independent data are available for two facilities, but yet not modelled). In the interest of brevity, I will move directly to a summary table of preliminary results to date as shown in Table 2, and then offer some commentary and perspectives.

Table 2: Summary table of preliminary M&V energy savings and attribution for Atrium Health

This experience at Atrium indicates that quantifying energy savings for behavioral interventions in C&I facilities is not necessarily any more difficult than doing so for traditional equipment retrofits. The biggest challenge, in my view, is establishing attribution of M&V energy savings to a specific influence. Attribution of energy savings needs to be carefully assessed. As shown in Table 2, savings for Atrium Sites 3 and 6 are attributed to Energy Connect because there are no other known interventions which could explain the energy savings (i.e. the capital upgrade or RCx programs). For Sites 1, 2, 4, and 5, the attribution of energy savings is being reported as attributable to the combined influence of Energy Connect plus capital and/or RCx interventions which overlapped the Energy Connect baseline or reporting periods (for this project, none overlapped the baseline period, but several projects overlapped the reporting period). Reporting of M&V energy savings as being influenced from multiple programs may be undesirable for program managers who are tasked to quantify energy savings from their program. However, if the influence of multiple programs cannot be separated, then the M&V analyst has no scientific basis to support reporting of savings for each program independently.

One approach to this attribution dilemma is to simply assume that non-behavioral projects or programs are independent, subtract the energy savings attributable to the capital or RCx projects from total savings, and report the remaining savings (if any) as attributable to the behavioral intervention. This is the approach used for Bonneville Power Authority’s (BPA) SEM program.6 There are two potential shortcomings of this approach.

The first shortcoming is that savings of non-behavioral interventions might exceed total energy savings determined using a whole-facility model approach. This is the case with BPA’s impact evaluation where the savings from an MT&R model for some facilities were less than capital project savings estimates, implying negative energy savings from the SEM. While these results were appropriately interpreted in the BPA report, there may be additional approaches. One way of reducing the risk of such outcomes could be to require rigorous M&V for the capital projects rather than relying on estimates of savings. In the case of Atrium Health, there are no available engineering estimates (to date) of energy savings for capital projects, let alone M&V determined savings. So unless the capital or RCx projects for each facility are subject to M&V determination of savings, any total energy savings will be reported as the combined influence of the multiple programs known to apply.

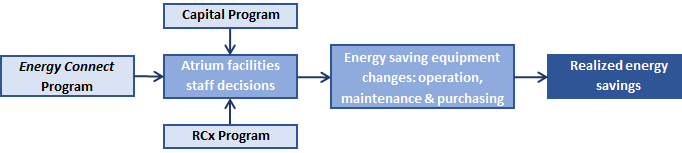

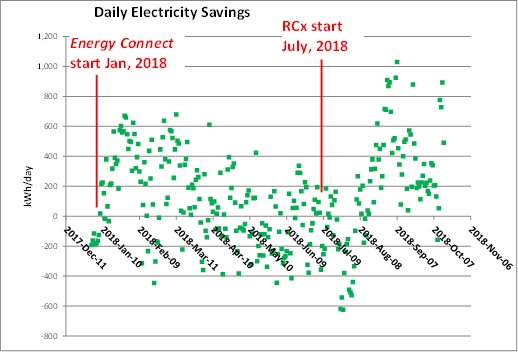

A second shortcoming of the subtraction approach described above, is that it implicitly assumes that the programs act independently to produce energy savings. However, in the case of Atrium Health (and probably in general), this is not likely. As conceptualized in Figure 1 below, the reality is that many (if not all) of the same staff who make decisions that lead to energy-saving actions are being influenced by up to three programs simultaneously. It is plausible, if not highly likely, that each program enhances the other. To illustrate, consider Figure 2 which shows daily electricity savings for Atrium Health Site 5. While a complete dissection of the results is beyond the scope of this article, it’s clear that energy savings were being achieved by Energy Connect, and then after a short period of RCx activity producing negative savings, even greater savings are indicated. It’s important to know that the same engineering and O&M staff are influenced by both programs, and there is no justification to support reporting savings separately. It might be tempting for the M&V analyst to set the initial Energy Connect reporting period as the baseline for RCx to report separate savings. However, this would not be supported from the perspective that not all six of the Energy Connect interventions were yet implemented, and the effects of behavioral interventions (e.g. training) should be expected to occur gradually over time and therefore continue to overlap the RCx activities. It is difficult if not impossible to prove, but it seems most likely that Energy Connect activity such as training improved the effectiveness of the RCx program, and probably vice-versa.

In conclusion, the experience with Atrium Health demonstrates that conventional IPMVP options can be employed for behavioral interventions, and for C&I applications these may be the only viable methods. Beyond quantifying energy savings, I suggest that establishing attribution of those energy savings to a specific program implemented at a given facility may be the most complex task. When multiple programs or projects are simultaneously influencing the same actors at a facility, the most reasonable finding for an M&V analyst may be to attribute realized energy savings to the combined effects of multiple programs.

Figure 1

Diagram illustrating program influence on facility staff, ideally leading to staff decisions and actions to change operating variables, improve maintenance practices, and/or adapt purchasing practices to save energy.

Figure 2

Atrium Health Site 5 daily electricity savings using an Option C model, illustrating the interactions between Energy Connect and RCx activity at this facility.

REFERENCES:

1. For definitions of behavior change, behavior changer, energy behavior and other key concepts, see the International Energy Agency Task 24 Toolbox at www.ieadsm.org/wp/files/Subtask-8-Toolkit-for-Behaviour-Changers1.pdf.

2. Cinner (2018) “How behavioral science can help conservation” Science V362, issue 6417, p. 889

3. Atrium Health results described here have been publicly presented at the World Energy Congress in Charlotte, North Carolina, October, 2018. “M&V Energy Savings for Behavior Change Energy Savings in Six Healthcare Facilities” by Mazzi, Cowan, Ratner, and Roberts.

4. OPA (Ontario Power Authority). 2017. “Protocols for Evaluating Behavioral Programs” (downloaded March, 2017) http://www.ieso.ca/-/media/files/ieso/document-library/conservation/ldc-toolkit/emv-protocols-and-requirements-10312014.pdf?la=en

5. Cowan, Sussman, Rotmann & Mazzi (2018) “It's Not my Job: Changing Behavior and Culture in a Healthcare Setting to Save Energy ”ACEEE Summer Study, At Monterey, California.

6. SBW Engineering & The Cadmus Group (2017) “Industrial SEM Impact Evaluation Report” prepared for Bonneville Power Authority.

(*) Eric Mazzi, PE, PhD, CMVP, is the owner of Mazzi Consulting Services. Eric is also a member of the EVO IPMVP Committee and an EVO L3 instructor.