By Denis Tanguay*

As an economist, and for self-defense purposes, I learned early enough in the profession that the best way to protect oneself against the judgment of others was to learn as many jokes as possible about economics and its methods. If you have two economists in a room, how many opinions will you get? Three. If an economist tortures stubborn numbers long enough, they will inevitably speak.

Of course, these jokes equally apply to statisticians and probably to other professions as well. But what about this one?

An economist, an engineer and a physicist are lost in the woods with only canned food but no can opener. To access the food, the engineer will probably hit the can with the largest possible stone he could find until it opens with the can content most likely to splash all over. The physicist will throw the can in the air and calculate how high she should throw it so when gravity takes it back on the ground it will break opened and produce a similar result as for the engineer. The economist will just assume he has a can opener, state that all other variables are held constant and wait to see what happen. Of course, the correct solution to this starvation challenge is that you scrape the top of the can on a rock until the metal is worn enough so you just need to lift the lid with your fingers and enjoy your meal. I tried it and it takes about five minutes – or ten or fifteen, depending on your motivation and your hunger.

With a little bit of imagination, human beings can accomplish great things. If they add more thoughts to their initial accomplishments, they can take resulting outcomes to stellar levels. With even more imagination, a few ounces of scientific methods and the correct hypotheses, they can even accomplish the impossible, literally. They can even confirm that deemed energy savings are real. This is not me saying.

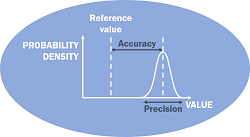

I am writing this text sitting at a coffee shop at the Copenhagen airport. I could not help but write my thoughts about something I heard at a conference. One speaker on a panel was proudly talking about his energy efficiency projects in a country I will not name. The room was filled with energy efficiency aficionados. Top level for the most part. With no warning, the panelist proudly reported that the science-based approach and statistical methods used to calculate deemed savings on their projects was 100 % accurate. Not in those exact words, I confess. But after consulting many attendees after the talk, I collected enough testimonies to assert that we all heard the same things.

In retrospect – a short one admittedly – I am not sure what I found the most disturbing in this situation: the statement about accurate deemed savings or the apparent lack of reaction from most of the people in the room. Both are definitely and somewhat equally disconcerting.

One of the most ov erused citations in energy efficiency is from Sir William Thomson. If this name doesn’t ring a bell, he was better known among scientists as Lord Kelvin. Forgive me for using it again but I feel it is quite relevant to this article. On May 3, 1883, in a lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers, he declared that “...to measure is to know...” and that “...if you can not measure it, you can not improve it.”1 Lord Kelvin must have been right. After all, he was a true man of science. But no human being conceals the absolute truth about everything. And for those readers who have doubts about this, here’s a little less known quote from Kelvin: “Heavier than air flying machines are impossible.”2 The legend goes that this statement was the result of a personal feud with the chairman of the nascent Aeronautical Society. Kelvin was of course proven wrong – monumentally wrong.

erused citations in energy efficiency is from Sir William Thomson. If this name doesn’t ring a bell, he was better known among scientists as Lord Kelvin. Forgive me for using it again but I feel it is quite relevant to this article. On May 3, 1883, in a lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers, he declared that “...to measure is to know...” and that “...if you can not measure it, you can not improve it.”1 Lord Kelvin must have been right. After all, he was a true man of science. But no human being conceals the absolute truth about everything. And for those readers who have doubts about this, here’s a little less known quote from Kelvin: “Heavier than air flying machines are impossible.”2 The legend goes that this statement was the result of a personal feud with the chairman of the nascent Aeronautical Society. Kelvin was of course proven wrong – monumentally wrong.

This somewhat created doubts about Kelvin’s wisdom. Kelvin was a mathematician and a physicist. Clearly, a man of great and vast knowledge. But as an economist, I have to be loyal to my profession. I was only reassured about Kelvin’s citation – not the one about flying machines, the measurement one – when I found this one from one of my peers, Frank Hyneman Knight: “If you cannot measure, measure anyhow!”3 A very interesting statement, and particularly inspirational in the context of the IPMVP. Those six simple words (five given the repetition) are the foundation of the IPMVP. A-B-C-D, the four IPMVP options all require some form of measurement – no matter what. The protocol doesn’t say how, but it says you must.

I will here ask the readers to put their personal beliefs aside for a moment and accept the idea that implementing an energy conservation measure (ECM) is a contract in the broadest possible sense. For a short moment, we will all believe in the same god. We economists like to make hypotheses. That’s what helps us look more scientific than we are in reality. But this is a debate for another forum.

When a government designs and implements an energy efficiency program, it is taking money from the entire taxpayer base to provide financial assistance or grants to those directly benefiting from these programs. They do that because they argue that ECMs implemented only by a small portion of citizens will generate benefits for the entire taxpayer base. This is clearly a social contract which deserves to be executed not only in good faith but with common sense and proper due diligence. And common sense necessarily implies there will be some form of performance measurement and verification.

Taxpayers in every single country expect – rightfully – that this money is invested, not spent. Investment requires a return – not only the hope of a return as I recently read in the description of a program proposed by a government somewhere in North America. And to guarantee a return, you need to measure and verify how the money was spent. In our context, we want to know if the ECMs were really implemented, as a start and, above all, we want to know if they are performing up to initial program expectations. This is clearly not unreasonable.

Of course, some governments will “measure” the success or their program just by reporting the amount of money they spent on them. They have no shame in making Twitter-like statements such as: “We spent 100 million on energy savings measures – a big success.” Strange metrics. There is no way anyone can seriously argue that savings will be achieved if not assessed based on some form of measurement and verification. In this context, we can formulate hypotheses about savings but that’s about all we can do. Impossible to calculate the return on investment. As far as I am concerned, I could say that this is money wasted and thrown out the window and in context my argument is as valid as the government claiming success. Governments behaving in this manner are not respecting their moral contracts with taxpayers. At the end of the day, they are just imposing another black-eye to the energy efficiency industry.

The same is true for utilities. I could rewrite the previous paragraphs and replace taxpayer by ratepayer and I would arrive at the same conclusion. Or maybe not. Let’s agree on similar conclusions for the time being while knowing that utilities, contrary to most governments must have their programs dissected by public utility boards. Their programs are usually analyzed through public hearings and challenged by intervenors and expert witnesses. It is more difficult for utilities to report success based on deemed savings. But this system is far from being perfect. And I underline the fact I just wrote “more difficult” - not "impossible". The truth of the matter is many utilities – not out of malicious thinking but often by mere ignorance or overconfidence in third parties’ assessments – will report deemed savings as true-verifiable-science-based savings. Deemed savings are guesses – educated guesses, sometimes, but guesses anyway – and they can’t be measured and verified.

Suppose you want to buy my house. Would you trust me 100 % if I tell you there is nothing to worry about? Probably not. If you do, I would think you are stupi d. Not because I am lying to you. Just because there are things that I may not be aware regarding the condition of my house. Common sense would dictate that you would likely hire a building inspector to check and verify the condition of the house. Why? Because we are just about to enter into a contract and you want to protect yourself...and your investment, and, as a positive side effect, our friendship. Without proper assessment and verification, we could both end up in court. Why would that be different for the investments the governments or utilities are doing you your behalf with energy efficiency programs?

d. Not because I am lying to you. Just because there are things that I may not be aware regarding the condition of my house. Common sense would dictate that you would likely hire a building inspector to check and verify the condition of the house. Why? Because we are just about to enter into a contract and you want to protect yourself...and your investment, and, as a positive side effect, our friendship. Without proper assessment and verification, we could both end up in court. Why would that be different for the investments the governments or utilities are doing you your behalf with energy efficiency programs?

I left the Copenhagen airport some paragraphs ago and I am past Heathrow airport in London where I just made my connection. Only had time to write a few lines and write a tiny bit of another paragraph. My concluding remarks are therefore written while the plane is just about to enter the Canadian airspace east or Newfoundland and Labrador at 36,000 feet. Deemed savings can only guarantee one outcome: that the savings are precisely and accurately unverifiable. As stated earlier, the IPMVP only has four options: A, B, C and D. While deemed savings may have some utility in special circumstances, within the IPMVP framework and for the purpose of measurement and verification, option “E” stands for “error”.

END NOTES

1. For the nerdy readers, here is a longer contextual quote on the same topic from Lord Kelvin which was part of his May 3, 1883 lecture. “I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it, but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely in your thoughts advanced to the state of Science, whatever the matter may be.

2. http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/biography/Kelvin.html

3. Knight, Frank Hyneman. 'What is Truth' in Economics? (1956)

Table of content illustration: Pixabay.

(*) Denis Tanguay is the Executive Director of EVO.